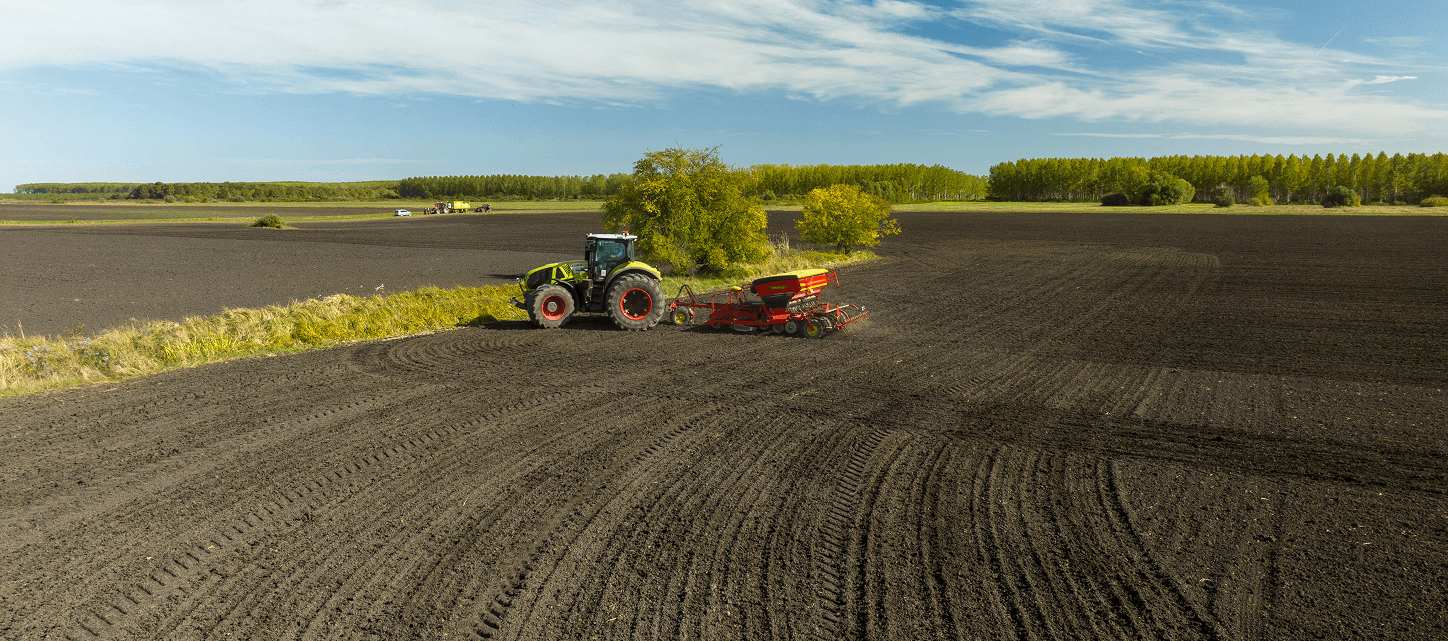

The area is characterized by a continental climate with four distinct seasons. Long-term climate normals indicate an average annual precipitation of approximately 550 mm and a mean annual air temperature of 11 °C.

However, during the recent period 2021–2025, weather conditions deviated from these long-term averages. Mean annual precipitation declined to 431 mm, while the average annual air temperature increased to 13 °C. Summers are typically hot and dry, and precipitation is unfavorably distributed throughout the growing season. The dry period is not limited to July and August, but commonly begins already in June, increasing the frequency and intensity of early-season water stress for crops.