How We Tackle Weeds in Organic Chickpeas

June 23, 2025We’re back in the field with our chickpea cultivation series! See how we tackle weeds after emergence using inter-row cultivation.

Read articleHave you ever considered ‘ground moving’ to prevent flooding in your fields? We did, and we share what we’ve learnt.

What do you imagine the term ‘ground moving’ to include? Moving soil from one end of the field to the other with a spade? Well, it’s a bit more complicated than that, but is very useful to prevent flooding in your fields. We, at LoginEKO, have experienced this problem in several locations. One was particularly challenging, and led the team to search for a new and efficient solution.

Slobodan Jocić is the Lead for Data Acquisition at LoginEKO, and the man who had to find a solution for a field that was partially without yield due to ponding. This affected approximately 20% of a 68-hectare field: “The rainy season of January 2021 was particularly significant because the damage to the winter wheat crop was really high.” Slobodan starts to explain. “If the plant remains underwater for even one day, the yield will decrease by 30%. If this continues for the next three days, the yield will be lower by 40%, and eventually, there will be no yield.”

How did our team prevent the worst case scenario? They considered several solutions, such as drainage systems – that weren’t possible due to the lack of canals and the width of the field. Filling the lower levels with soil was too expensive, so they turned to ground moving or soil flattening.

To prevent the worst outcome, Slobodan and his team explored various solutions. One option was to install drainage systems, which involved placing parallel pipes at 15- to 20-meter intervals that would drain water from the surface to subsoil levels, and eventually into nearby canals. However, this solution was not feasible because there were no existing canals, and the field was too wide to allow for the necessary slope of the pipes. Another solution they considered was filling the lower levels of the field with external soil, but they determined that this would be too expensive. Finally, they turned to ground moving, also called ‘dirt moving’ or ‘soil flattening’ by some companies.

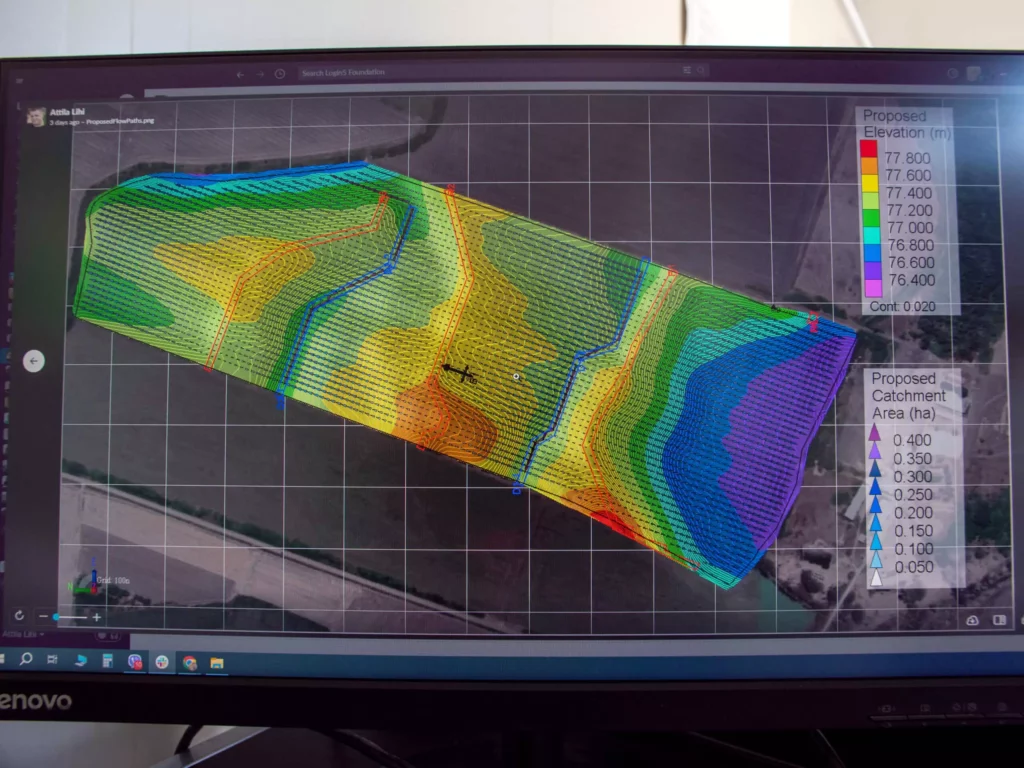

“I would describe ground moving as creating a more suitable landscape for crop growth by directing water towards a lower point until it ends outside of the field in the surrounding canals or, if there are no canals, to the point where one can install drainage pipes,” Slobodan explained. His team found an Earthworks System company that could design a surface drain network to remove excess water for LoginEKO that used a less invasive landforming method with a minimal slope of 0.5% and respected the natural landscape –as well as LoginEKO’s sustainability efforts. This is not as simple as it sounds: “The ground moving process is delicate to preserve the fertile top layer, which varies from 20 to 70 cm in the field. Digging too deep could result in infertile soil.”

To avoid that, the Earthworks System company proposed several options after making calculations using the elevation data we gave them. According to Slobodan, the elevation data can be extracted from data acquired by tractors, drones, or LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) sensors mounted on planes. They used the last one, because it’s also the most precise method for obtaining elevation data for the fields, buffer zones, and surrounding canals.

The company proposed around 10 models based on elevation data, taking into account the so-called ‘tramlines’ of the field (a kind of ‘small dune’), logistical limitations, costs, and preserving fertile soil. The LoginEKO team then chose the best model and leveled the ground from the highest to the lowest points of the field, while considering the maximum cuts and the presence of tramlines that couldn’t be altered.

Were there any challenges while implementing the solutions? Slobodan smiles: “We didn’t expect everything to go smoothly. Integrating their software with ones that we were already using posed challenges since nobody in the region had prior experience with it. Despite being pioneers, we succeeded in making it work, so that was really nice.” Additionally, the team faced issues in a part of the field where the soil wasn’t removed after a canal was cleaned some 20 years ago, and needed external help to remove the dry soil from the top.

Slobodan is nevertheless pleased with the solution, though the work isn’t finished yet. The field has been extended to 69.2 hectares by scraping the banks of the canals and eliminating ponding areas: “The field now has a natural slope towards the edges because of the smallest ground moving, and there was no ponding during the last rain.” The first results were seen during the rainy period from November to March, and also in April and May. It turned out we had some ponding next to the canals, but much less than before.

Slobodan acknowledges that there are still some small parts of the field that need correction, but this is a natural process of soil subsidence and it’s expected with a large field. That’s why we plan to repeat the process of ground moving for problematic areas. The team also plans to investigate how this technique affected soil microorganisms’ respiration with the help of the LoginEKO Agronomy Research and Development team. If successful, they plan to productionize it and make it available to others by creating instructions for farmers. Will these potentially save others time and money? “Yeah. That’s my idea. I mean, that’s the idea of everything we do here. We share our good practice with everyone and the practices have to be profitable to be adapted by others.”

You can read more about, how we implemented ground moving to our field production here.

We’re back in the field with our chickpea cultivation series! See how we tackle weeds after emergence using inter-row cultivation.

Read articleTwo days, three farms, one shared goal: growing hemp more sustainably. Here’s what we learned and shared during our tour of Prekmurje.

Read articleChickpeas offer great potential for organic farming. Join us as we walk you through the essential steps of chickpea cultivation, starting with seedbed preparation.

Read article